Does Israel have more to gain or to lose from the rise of the far-right in Austria?

REPRINTS FROM THE JERUSALEM REPORT; BY GOL KALEV, NOVEMBER 4 , 2017

Related article: The Resurfacing of European Colonialism

Heinz-Christian Strache, the head of the far-right Freedom Party, celebrates in Vienna with his wife, Phillipa Beck, after Austria’s general election. (photo credit:MICHAEL DALDER/REUTERS)

Heinz-Christian Strache, the head of the far-right Freedom Party, celebrates in Vienna with his wife, Phillipa Beck, after Austria’s general election. (photo credit:MICHAEL DALDER/REUTERS)

SOMETHING IS changing in Europe. A debate on the character of the continent is being deliberated in a series of national elections.

In the October 15 Austrian elections, the far-right Austrian Freedom Party made significant gains, rising from 20.5% to 26% of the vote, and entered negotiations to join the government of 31-year-old chancellor- elect, Sebastian Kurz.

Whereas in Germany, the Alternative for Deutschland far-right party is relatively new, having entered parliament for the first time after the September 24 election in which it garnered 13% of the vote, Austria’s Freedom Party has a long history. That history is stained with antisemitism and racism, with Nazis and neo-Nazis among its members and even its leaders. When the party entered the government in 2000, much of the international community, including the European Union and Israel, decided to boycott Austria.

The possibility of the Freedom Party entering government again has sounded alarms across the Jewish world.

Oskar Deutsch, a leader of the Jewish community in Vienna, expressed his strong opposition to the Freedom Party in a Facebook post: “Nearly every day a racist individual case comes up, deputies who spread antisemitic conspiracy theories… Their representatives mourn the liberation of Europe in 1945 as a defeat.”

Indeed, the Israeli government does not currently engage with the Freedom Party, but some think this should change. MK Yehuda Glick (Likud) has held extensive meetings with Freedom Party leader Heinz-Christian Strache, whom he has described as “a good man, deeply connected to the Bible.”

According to Glick, the Freedom Party has changed for the better. “Strache cleaned up the party. He spent seven years fighting within the party to get rid of antisemitic and neo-Nazi elements. He did a thorough job.”

Others are skeptical and maintain that the changes are cosmetic, pointing to individual cases as indicative of a pervasive antisemitism in the party.

Charles Small, founder and director of the Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy, insists that opposition to the party must be unequivocal. “There should be zero tolerance for antisemitism, especially from Austria given its horrific past,” he says.

Strache visited Israel on a number of occasions and asked Glick to convey a letter to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu expressing his support for moving the Austrian Embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

The Austrian media have mocked such visits and contacts as attempts for securing a “kosher certificate” for the party’s messages of hate.

“The Freedom Party is not only antisemitic, but it is against basic democratic principles,” warns Small. “It uses terms such as ‘pure Europeans’ and does not see humans as humans.”

Indeed, Glick spent much of his time with Strache discussing the party’s views on Islam.

“Strache clarified that he has nothing against Muslims and supports a dialogue,” Glick says. “He pointed to the reality that already 10% of the population is Muslim and 50% of first-grade students in Austria are Muslim.”

Strache told Glick that when certain Muslim countries in the Middle East fund the construction of a mosque in Austria, they later pay for the establishment of various institutions around that mosque, such as charities, non-governmental organizations and cultural centers. Others on the European Right and Left claim similar realities exist throughout Europe.

Just like in the German elections, analysts say, much of the vote for the far-right in Austria was driven by the fear that Muslims will replace “white Europeans.”

The immigration trend of Muslims to European countries coupled with their high fertility rate have aggravated that fear.

At the same time, the population of non- Muslim Europeans is shrinking, due to low birthrates. In addition, postwar Europe is post-ideological, secular and universalist, while Muslims tend to have a strong ideology, religion, particularity and willpower.

In addition to demographic and narrative elements, the fear is augmented by an alleged institutionalized mechanism driving the replacement trend. According to Strache, Muslim governments are funding parallel communities in the heart of Europe.

In a sense, it is a form of reverse colonialism. Time will tell if such views are symptoms of Islamophobia and paranoia or if we are witnessing early stages of a “war for European succession,” with the seeds of its institutional, financial, philosophical, military and political infrastructure already in place.

Fear of Islam figured prominently not just in the Freedom Party’s platform, but also in the campaign of the center-right Austrian People’s Party, which won the election, capturing 31.5% of the vote, up from 24% in 2013.

THE AUSTRIAN Jewish community, which is estimated to be under 10,000, is concerned that in response to the perceived Islamic threat, there might be a crackdown on religious schools and rituals as a whole.

Such actions could adversely affect Austrian Jewish life, for example, when it comes to kosher slaughtering and circumcision. But of even greater concern is the historical pattern that when things go bad, Europeans tend to direct their frustrations at the Jews. Indeed, some believe this is already happening.

Anti-Israel demonstrations have become more passionate, and the battle cry of young white Europeans has shifted from “End the occupation” to “End the genocide in Palestine.”

A growing hostility toward Israel on the street has been accompanied by an escalation of official support for anti-Israel measures within the EU and by some European governments, including initial support by France and Sweden of a UNESCO resolution suggesting there is no Jewish connection to the Temple Mount. There has also been increasing animosity toward Israel in the European media and the salons of the European establishment.

Given that such dynamics mostly emanate from the Left, should Israel continue to boycott the Austrian far-right, which is now expressing strong support for the Jewish state? Or, should it engage in dialogue with it and other populist right-wing parties in Europe? “We cannot sacrifice our values for short term gains,” says Small. “Nothing good comes of hate.”

Like others in the Vienna Jewish community, Deutsch is firm in his opposition to the Freedom Party: “When the nationalist wolf puts on a blue sheepskin it does not change its nature, only its appearance,” he says, referring to the party’s blue color scheme.

Without a doubt, the memory of the Holocaust is strongly rooted in the Israeli and Jewish ethos. It is not only about the mass murders and the death camps, it is also about Jews having forged long-lasting friendships with seemingly well-mannered Europeans, who, when the opportunity presented itself, brutally turned against them.

The question is how does one apply the memory and its lessons to the current situation in Austria? Is there a tendency to overplay the threats of the past, and underplay the dangers of the present? A similar question has arisen in Austria’s past.

In 1895, Vienna elected an openly antisemitic mayor. The emperor and prime minister decided to intervene, refusing to confirm Karl Lueger to office.

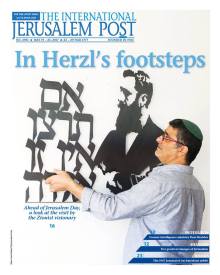

Most Jews celebrated the decision, but one Viennese Jew was not among them. Theodor Herzl, the father of political Zionism, wrote at the time, “Many Jews rejoice foolishly about not accepting Lueger as mayor. As if antisemitism equals Lueger. On the contrary, I believe that the movement against the Jews will only be strengthened.”

Lueger was a staunch antisemite. Herzl even considered challenging him to a dual.

And yet, Herzl recognized that applying a stance of zero tolerance to antisemitism would have a price. He arranged a meeting with then-prime minister Count Kasimir Badeni, where he warned, “If you deny him, you will be responsible for the whole of Jew hatred.”

After winning repeatedly, Lueger was eventually confirmed. In the interim, hate against Jews mushroomed. Herzl carefully observed how Europe was changing in the 1890s and applied it to understanding shifts in sources and motives of Jew hatred.

The recent Austrian election beckons us to remember Herzl as we assess the contemporary threats emanating from Europe.

“There is a tendency in Israel to ignore antisemitism on the Left and to condemn antisemitism on the Right,” says Glick.

“The Right in Europe is getting stronger and stronger. It does not make sense for us just to dismiss it.”

Related articles by Gol Kalev:

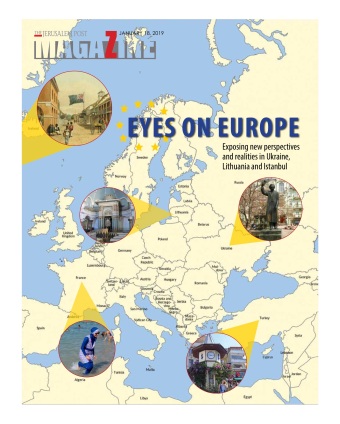

The Resurfacing of European Colonialism

Prime-Minister Morawiecki: Poland fully supports Israel’s sovereignty

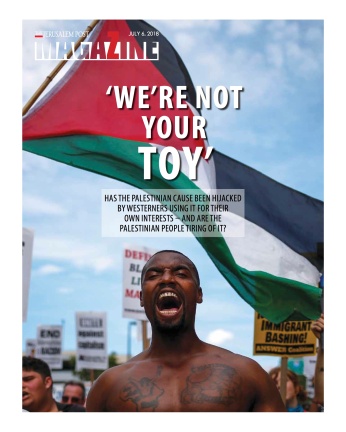

We’re not your toy: Europeans hijacking the Palestinian cause

More on Herzl:

Zionism and Herzl between France and Britain

Herzl vs Ahad Ha’Am – Outsider vs Establishment

Herzl and the first Zionist Congress

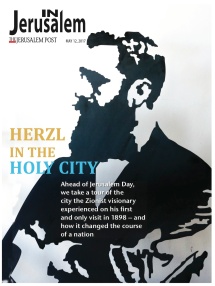

Herzl’s Jerusalem visit – an inflection point in Zionism

Fulfillment of Herzl’s utopia: The first electric train reaches Jerusalem!

Jewish transformation – Judaism 3.0

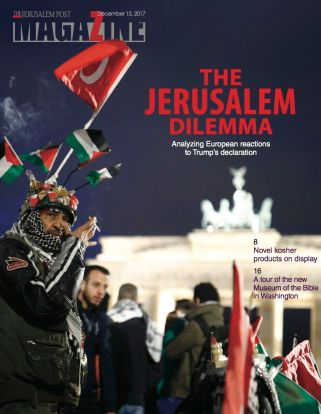

More by Gol Kalev: Europe and Jerusalem

on European involvement: Europe

on Jerusalem and Zionism: Jerusalem

For inquiries and comments, please email: info@europeandjerusalem.com

We would be happy to hear from you.